Tobias Birgerson ställer ut ”The Toolness of Things” i en internationell utställning med verk från HDK och Stenbyskolan. Utställningen är en del av Ferrous 19 och visas på Maylord Shopping Center i Hereford mellan den 5e och 14 april. Öppent 11-16.

Nedan skriver Damian Skinner om Tobias föremål i utställningen.

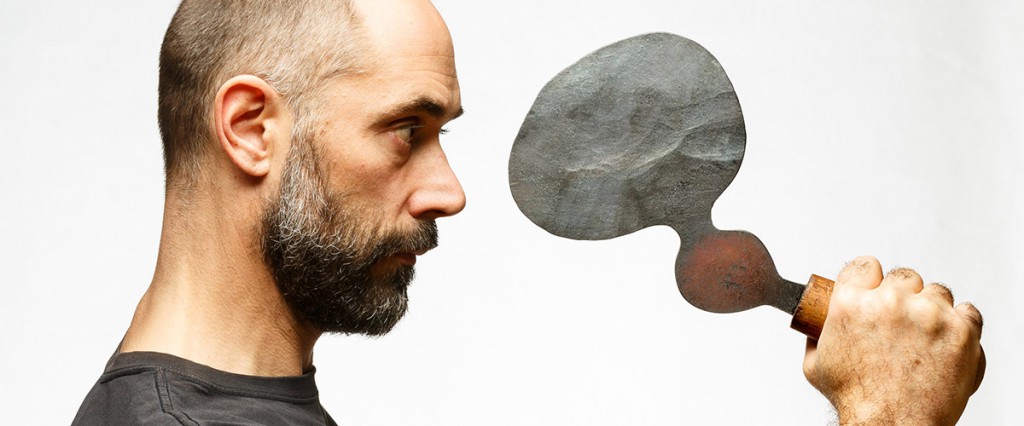

What are they? They are forged steel forms, flattened planes of metal forming a wonky gourd silhouette, that have been attached to wooden handles. While they follow the same general pattern, each of them is different: the size and angle of the swelling double circles that make up the gourd silhouettes are idiosyncratic; the wood grain and details of the handles are subtly altered.

They are objects that appropriate the signs of tools, and by extension the signs of blacksmithing. The steel has been forged, and the wood has been turned, just like real tools made of these materials. But these objects don’t have a function. They are tool-like: the right size and weight to be a tool, held in the hand just like a tool, robust and hard-wearing like a tool, but ultimately there is no use for them, no action they undertake or problem they solve.

This is why I use the term ‘appropriation’. These aren’t beautiful or exquisite tools, adding a big dose of art and skill to heighten the often-overlooked aesthetics of functional, everyday objects. These objects stage a deliberate gap between themselves and the things they reference. The overt marks of beaten steel in the metal silhouettes aren’t just the effects of a particular process that is the most successful or appropriate way to forge this shape, but they are cultivated as an end in themselves, to evoke the category of blacksmithing. The size and weight of these objects aren’t arrived at because they aid function and effectiveness, but because they conjure sense memories of holding and working a general category of tools.

These objects are made and presented in a series. There is more than one of them, and this seems important somehow. Because they are idiosyncratic, there is a danger that just one will seem frivolous or superficial. A group reinforces their seriousness, enforces their status as a position or a statement. Together, they claim or mark out a territory that is parallel to and in dialogue with the category of tools, but an accumulation of them also emphasises the ways in which they differ from tools.

These objects exist as Tobias Birgersson’s declaration of where the integrity of blacksmithing might lie in the twenty-first century, in a time when the historical purposes of blacksmithing have been rendered obsolete, and the opportunities of studio craft are limited to precious non-functional objects for the home, and the idea of blacksmithing as sculpture results in bad, large public art. Blacksmiths can still make bespoke functional objects – like gates – for appreciative and wealthy clients. But in what ways can blacksmithing as both materials and techniques and a mode of thinking and making assert itself in relation to an awareness of fine art and contemporary thinking about craft?

This is the place that these objects exist.

Text by Damian Skinner. Damian Skinner is an art historian and curator based in Gisborne, New Zealand. He edited the book Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective (Lark Books, 2013). They talk frequently about craft.

Photos by Christian Habetzeder.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

They are objects that appropriate the signs of tools, and by extension the signs of blacksmithing. The steel has been forged, and the wood has been turned, just like real tools made of these materials. But these objects don’t have a function. They are tool-like: the right size and weight to be a tool, held in the hand just like a tool, robust and hard-wearing like a tool, but ultimately there is no use for them, no action they undertake or problem they solve.

This is why I use the term ‘appropriation’. These aren’t beautiful or exquisite tools, adding a big dose of art and skill to heighten the often-overlooked aesthetics of functional, everyday objects. These objects stage a deliberate gap between themselves and the things they reference. The overt marks of beaten steel in the metal silhouettes aren’t just the effects of a particular process that is the most successful or appropriate way to forge this shape, but they are cultivated as an end in themselves, to evoke the category of blacksmithing. The size and weight of these objects aren’t arrived at because they aid function and effectiveness, but because they conjure sense memories of holding and working a general category of tools.

These objects are made and presented in a series. There is more than one of them, and this seems important somehow. Because they are idiosyncratic, there is a danger that just one will seem frivolous or superficial. A group reinforces their seriousness, enforces their status as a position or a statement. Together, they claim or mark out a territory that is parallel to and in dialogue with the category of tools, but an accumulation of them also emphasises the ways in which they differ from tools.

These objects exist as Tobias Birgersson’s declaration of where the integrity of blacksmithing might lie in the twenty-first century, in a time when the historical purposes of blacksmithing have been rendered obsolete, and the opportunities of studio craft are limited to precious non-functional objects for the home, and the idea of blacksmithing as sculpture results in bad, large public art. Blacksmiths can still make bespoke functional objects – like gates – for appreciative and wealthy clients. But in what ways can blacksmithing as both materials and techniques and a mode of thinking and making assert itself in relation to an awareness of fine art and contemporary thinking about craft?

This is the place that these objects exist.

Text by Damian Skinner. Damian Skinner is an art historian and curator based in Gisborne, New Zealand. He edited the book Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective (Lark Books, 2013). They talk frequently about craft.

Photos by Christian Habetzeder.